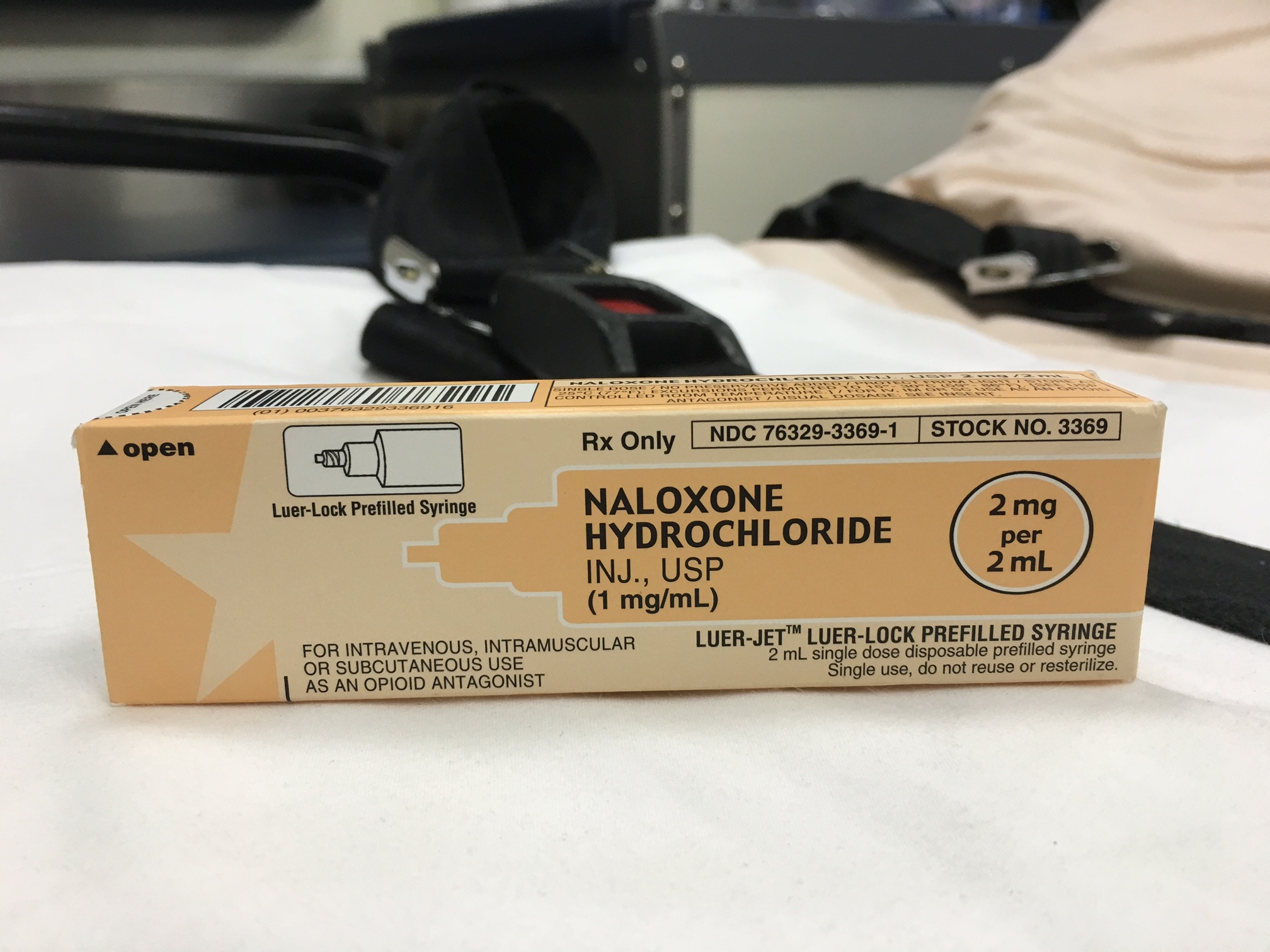

Is there an Irrational Fear of Naloxone?

In the U.S. there has been a 286% increase in heroin-related overdose deaths since 2002. In 2014, a total of 47,055 drug overdose deaths occurred. Our EMS systems and emergency departments have felt the surge, along with a corresponding increase in the use of the drug naloxone.

Community officials have taken the initiative to reduce the number of overdose deaths by making naloxone available through non-traditional means. However, this has not been particularly well received by members of the medical community, particularly pre-hospital providers.

Discussion of the proper use of naloxone often sparks a passionate, sometimes contentious debate, usually focused around the deleterious side effects and inappropriate use of naloxone.

Hopefully, a review of the literature will make providers less apprehensive about the expanded use of naloxone and spark a healthy debate of the current standard of care.

Treatment of an opioid overdose

A common strategy for treating an opioid-related overdose is to initiate BVM ventilation to treat respiratory depression and then titrating naloxone until the patient’s respiratory effort becomes adequate but not to the point of the patient becoming lucid.

Should patients be given enough naloxone to regain consciousness?

There was a time when I passionately advocated for allowing patients to remain somnolent in the setting of a suspected opioid overdose, but I changed my mind after encountering this emergency more frequently.

Like many things in medicine, it sounds good in theory, but it doesn’t translate easily into practice. Almost every attempt I made at titrating naloxone until the respiratory depression improved resulted in the patient becoming completely lucid.

What about adverse outcomes associated with naloxone administration?

Many emergency providers are apprehensive about giving naloxone due to undesirable side effects. Patients regaining consciousness after naloxone administration may experience many symptoms that are collectively referred to as Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (AWS).

Patients with AWS may exhibit nausea, vomiting, tachycardia, diarrhea, hypertension, nervousness, and restlessness. The degree of withdrawal symptoms is relatively proportional to the amount of naloxone given, so smaller amounts will normally result in less serious withdrawal symptoms.

Rare but serious complications like cardiac arrest, seizures, acute pulmonary edema, and violent behavior are sometimes offered as reasons for not using naloxone (or not giving enough for the patient to regain consciousness). However, it is likely that these complications have been overstated, as the evidence has not been reproducible.

Osterwalder (1996) investigated subjects treated with naloxone from 1991-1993. Six out of 453 patients experienced severe adverse effects. One suffered asystole, three generalized convulsions, one pulmonary edema, and one violent behavior.

However, Burris (2000) reported in the International Journal of Drug Policy that “more recent research suggests that complications are exceedingly rare, that past reports of complications may have been erroneous, or that complications occur, if at all, in patients with pre-existing heart disease”.

Yearly et al. (1990) conducted a retrospective study of over 800 prehospital records of patients who received initial IV doses of 0.4-0.8 mg of naloxone and found that no patients experienced ventricular tachycardia, fibrillation, or asystole. There was one generalized tonic-clonic seizure in a patient with a history of seizures. The authors concluded that smaller doses of naloxone are not warranted.

What if a patient refuses transport after regaining consciousness?

Typically patients are transported to the hospital after regaining consciousness following the administration of naloxone. However some patients refuse, against the advice of treating paramedics.

One might expect there to be a high mortality for patients who refuse transport, since it’s widely known that the half-life of naloxone is shorter than the half-life of the opioid. However, current data suggest that a patient can refuse transport without serious consequences.

In San Antonio, Wampler et al. (2011) conducted a review of 595 patients treated with naloxone in a large fire-based EMS system who refused transport to the hospital. The San Antonio protocol consisted of giving naloxone, 2 mg IM, 2 mg IV, and an additional 2mg IM with patient consent. None were found in the Medical Examiner’s Office database two-days after refusing transport. Although 9 of the patients subsequently died, the shortest time interval was four days after treatment.

Vike et al (2003) conducted another retrospective review comparing prehospital and medical examiner databases. In the prehospital database there were 998 patients who had received naloxone and refused transport. In the medical examiner’s database there were 601 recorded opioid overdose deaths. None of them had been treated with naloxone within 12 hours of death.

Conclusion

- Naloxone is a safe and effective treatment for opioid overdose.

- Expanded use of naloxone is unlikely to cause an increase in adverse outcomes.

- Criteria should be established to help predict patients that can safely refuse transport to the hospital.

References

Burris S, Norland J, Edlin B. Legal aspects of providing naloxone to heroin users in the United States. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2001;12(3):237-248.

Kim D, Irwin K, Khoshnood K. Expanded Access to Naloxone: Options for Critical Response to the Epidemic of Opioid Overdose Mortality. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):402-407.

Opioid OD patients revived with naloxone who refuse further treatment do not die. EMSWorld.com. 2016. Available at: http://www.emsworld.com/article/10284002/opioid-od-patients-revived-with-naloxone-who-refuse-further-treatment-do-not-die. Accessed July 12, 2016.

Wermeling D. Review of naloxone safety for opioid overdose: practical considerations for new technology and expanded public access. Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 2015;6(1):20-31.

Wampler D, Molina D, McManus J, Laws P, Manifold C. No Deaths Associated with Patient Refusal of Transport After Naloxone-Reversed Opioid Overdose. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2011;15(3):320-324.

Boyer E. Management of Opioid Analgesic Overdose. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(2):146-155.

Vilke G, Buchanan J, Dunford J, Chan T. Are heroin overdose deaths related to patient release after prehospital treatment with naloxone?. Prehospital Emergency Care. 1999;3(3):183-186.

Comments