This is the first post of a multi-part series reviewing the 2015 ECC Guidelines.

The eagerly awaited 2015 AHA ECC Guidelines have been published (see also ERC Guidelines 2015) and the internet is buzzing as paramedics, nurses, and physicians all over the world comment about what has changed and what has stayed the same.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Whatever your opinion about the routine administration of epinephrine for patients in cardiac arrest, one thing that is new is a section dedicated to systems of care and continuous quality improvement.

I think the ECC committee should be applauded for making this change.

It’s one thing to know what we’re supposed to do. It’s another thing to make our systems perform in such a way that we deliver those results on a routine basis.

That does not happen by accident! As they say in the Resuscitation Academy, “It’s not complicated but it’s not easy.”

Reference: Part 4: Systems of Care and Continuous Quality Improvement

The guidelines now recognize two distinct systems of care with separate chains of survival: one for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and one for in-hospital cardiac arrest.

Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Early 9-1-1

- Early CPR

- Early Defibrillation

- Effective Advanced Life Support

- Post-Cardiac Arrest Care

In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

- Surveillance and Prevention

- Prompt Notification and Response

- Early CPR

- Early Defibrillation

- Post-Cardiac Arrest Care

You can see the new “chains of survival” by clicking here.

In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Patients with in-hospital cardiac arrest require a system of surveillance and prevention so that prompt action can be taken.

Pre-Arrest Rapid Response Systems

The guidelines recommend various strategies to prevent delayed recognition of patient deterioration and the development of Rapid Response Teams (RRT) or Medical Emergency Teams (MET) to facilitate early intervention in the hopes of preventing cardiac arrest from occurring.

The guidelines also recommend increased use of Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) orders and palliative care services for patients who have reached end of life and for whom resuscitation attempts are likely to be futile or inconsistent with their goals of care.

These discussions should, whenever possible, occur before the cardiac arrest occurs.

My wife is an Acute Care Nurse Practitioner who works as a Hospitalist, so I am aware of how difficult, time consuming, and emotionally draining these conversations can be.

Perhaps this is why we have historically avoided them. Regardless, these are conversations we need to have with patients and their families.

Challenges Associated With In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

The guidelines note that even in high risk areas cardiac arrest is relatively infrequent and members of the care team may be different for every cardiac arrest (note the similarity to commercial aviation).

This highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaborative planning and practice to ensure a well-choreographed, high-quality resuscitation attempt.

Crisis Resource Management

The guidelines include a discussion of Crisis Resource Management (CRM) and mention the importance of leadership, communication, checklists, and cross-checks during a resuscitation attempt to improve performance.

Although the guidelines do not explicitly mention it, the authority gradient in medicine can interfere with optimal team performance when members of the care team to not feel empowered to speak up, share opinions, or take action without explicit direction from the physician.

Dedicated resuscitation teams, simulation, and debriefing can all improve the effectiveness of in-hospital resuscitation.

Post-Cardiac Arrest

The guidelines note that post-cardiac arrest syndrome plays a significant role in cardiac arrest mortality and that survival of patients who experience ROSC after in-hospital cardiac arrest ranges from 32-54% with higher volume and teaching hospitals having a higher survival rate.

Our patients require and deserve a collaborative and multidisciplinary team of providers, including cardiologists, interventional cardiologists, cardiac electrophysiologists, intensivists, neurologists, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

In the absence of these services the guidelines recommend interhospital transfer to ensure access to these resources.

Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

The guidelines indicate that out-of-hospital cardiac arrest affects 326,000 patients annually in the United States with an annual incidence of 132/100,000. That means you should see 1.32 cardiac arrests per year for every 1,000 people in your community.

Most EMS systems ought to be able to obtain data from their PCR systems with the standardization of the NEMSIS data set, but this is an alternate way to estimate the epidemiology of cardiac arrest in your community.

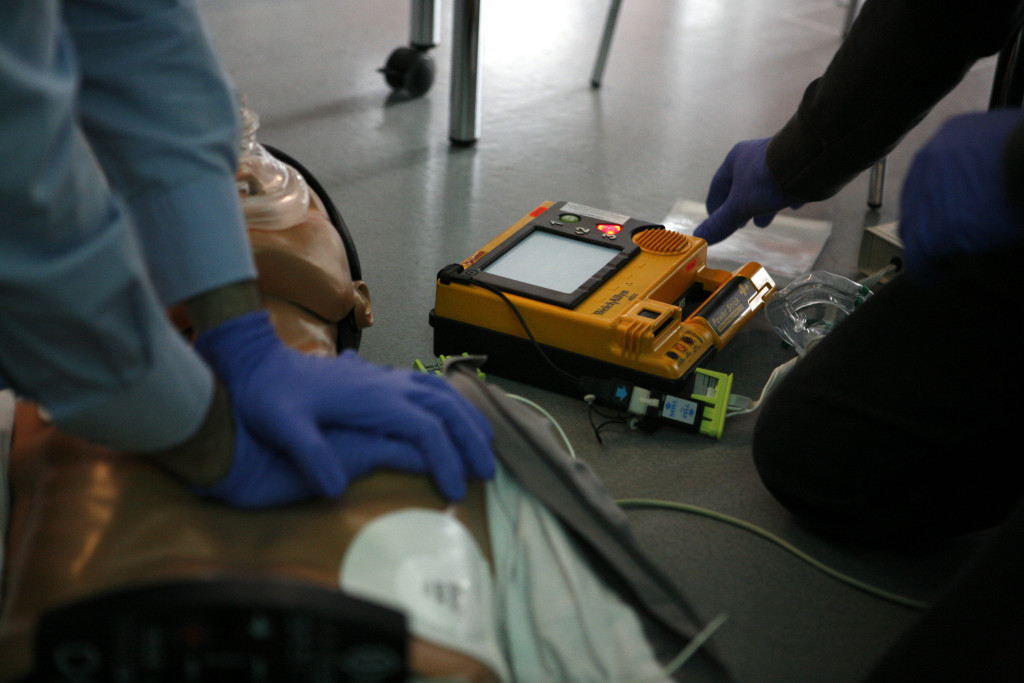

Public Access Defibrillation

The guidelines encourage public service access points (PSAPs) to know the locations of AEDs in the community so that dispatchers can direct bystanders to the nearest AED and assist in their use whenever possible.

There is more than one way to accomplish this task (including crowdsourcing) but one obvious step is the development of an AED registry.

Dispatcher Recognition of Cardiac Arrest

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Sudden cardiac arrest is often mistaken for falls, syncope, seizures, or other less serious medical conditions. As a result CPR can be delayed.

The guidelines recommend that dispatchers be specifically trained to identify abnormal breathing and agonal gasps.

When a patient is unconscious with abnormal or absent breathing it is reasonable to assume that the patient is in cardiac arrest.

Dispatchers should provide chest compression-only CPR instructions to callers for adults with suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

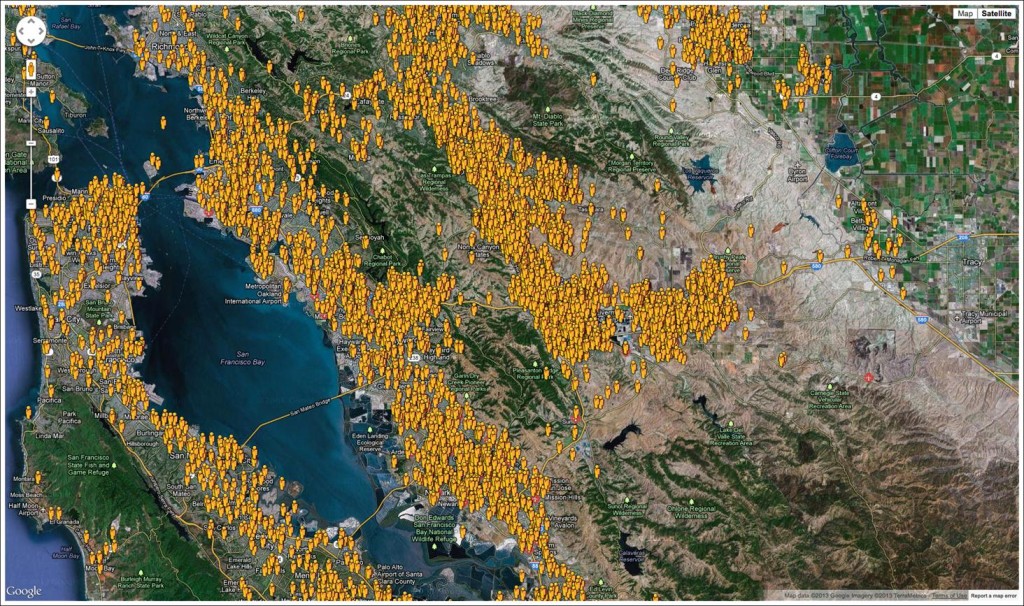

Use of Social Media to Summon Rescuers

The guidelines indicate that given the low risk of harm it “may be reasonable” to utilize social media based technologies to summon rescuers in close proximity to possible cardiac arrest victims.

The guidelines do not endorse a particular product or service but one of the best known notification apps is PulsePoint. They have two outstanding videos here and here. (No conflict of interest.)

Citizen rescuers awaiting notification from the PulsePoint app in Alameda County, CA (Image credit: Richard Price from the PulsePoint Foundation)

Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Quality Metrics

The guidelines encourage data collection using a simplified Utstein template. My department uses the CARES Registry.

This data collection allows EMS systems to find out how many cardiac arrests occur in their jurisdiction, how often the collapse is witnessed, how often bystanders perform CPR, and how often an AED is used.

In addition, it tracks the initial arrest rhythm, how often return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved, and most importantly, how many patients survive to hospital discharge with a CPC score of 1 or 2 (neurologically good outcome).

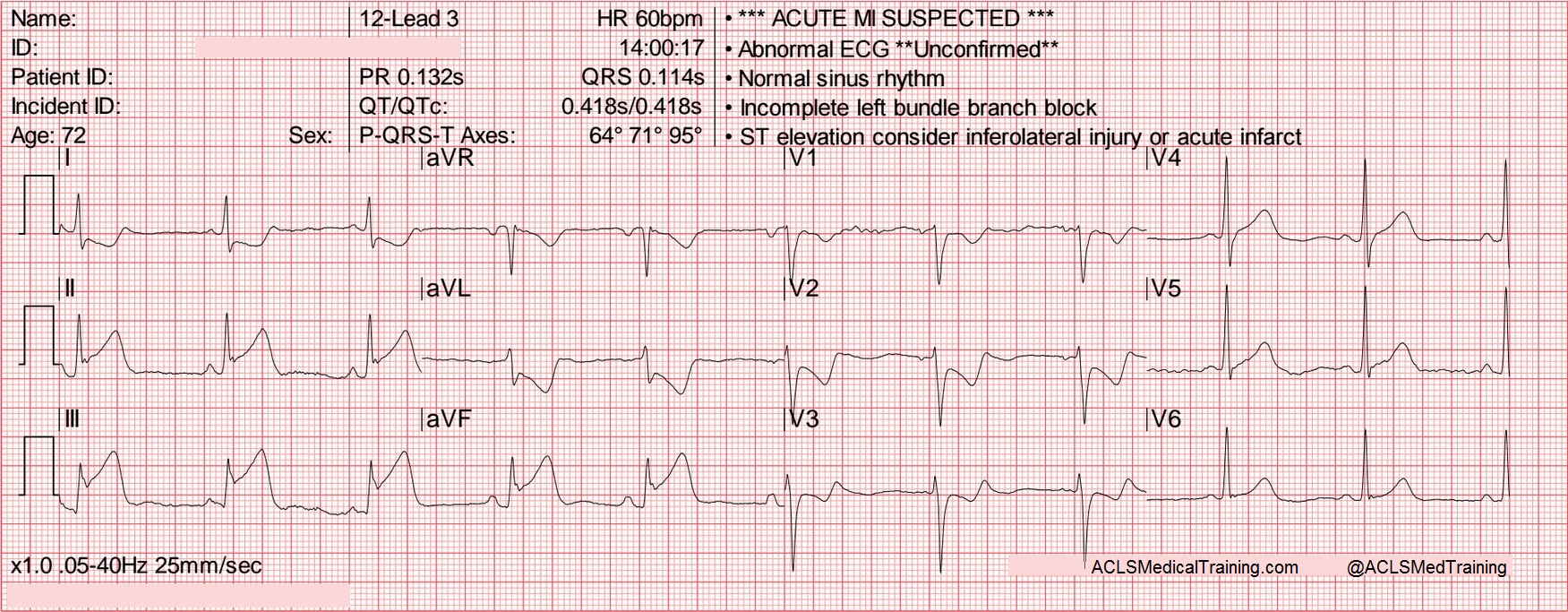

ACS and STEMI

Only 40-60% of STEMI patients contact 9-1-1 with the remainder self-reporting to the hospital.

Patients with possible ACS should receive rapid assessment that includes a prehopsital 12-lead ECG with an emphasis on early identification of acute STEMI and consideration of the method of reperfusion.

That may include prehospital fibrinolysis, notification to the hospital for early in-hospital fibrinolysis, and/or activation of the cardiac cath lab for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Transport to Specialized Cardiac Arrest Centers

The guidelines state that a regionalized approach to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest “may be considered” that includes transport to “cardiac resuscitation centers”.

Features of a cardiac resuscitation center:

- Evidence-based practice in resuscitation

- PCI capability 24 hours/day, 7 days/week

- Targeted temperature management

- Cardiorespiratory and systems support

- Adequate annual volume of cases to maintain proficiency

- Culture of continuous quality improvement

Continuous Quality Improvement

The guidelines discuss the importance of goal setting, measurement, and accountability.

Creative Commons: Diagram by Karn G. Bulsuk (http://www.bulsuk.com)

Many different scientific problem-solving methods exist which can be used to reduce variation and eliminate waste. They include:

- Lean

- Six Sigma

- Total Quality Management

- Plan, Do, Check, Act (or Adjust)

- Plan, Do, Study, Act

The exact method used is less important than having a system in place and developing a culture of continuous quality improvement.

As Mickey Eisenburg, M.D. likes to say, “Measure, improve. Measure, improve.”